The Greatest Trick The Supreme Court Ever Pulled Was Convincing The World …

Share this:

“The Greatest Trick The Supreme Court Ever Pulled Was Convincing The World Roe v. Wade Still Exists“

Share:

We first heard from Marni Evans a few days after she’d received an ominous voicemail. “I am calling from your doctor’s office,” the message began. An appointment for an abortion that Marni had scheduled for the next morning was suddenly canceled.

Marni isn’t the only woman in Texas who received such a call. On the last day of October, a conservative federal appeals court granted the state’s emergency request to reinstate part of an anti-abortion law that another judge had blocked just a few days earlier. That provision, which requires doctors who perform abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, will force many of the clinics in Texas to shut down. So, with the Fifth Circuit’s order in place, clinics had to start turning women away on the first day of November. Hundreds of women like Marni woke up to the news that their appointments weren’t going to happen.

Marni knew she still wanted an abortion — but she wasn’t sure if she would be able to get one in Texas. So she used her frequent flier miles to book a one-way ticket to Seattle.

“I thought that it would be a smart idea to just get out of Texas,” she explained. “I wasn’t sure what I would find at other Texas clinics because I was aware that over 100 women’s appointments had been canceled on the same day. And I was concerned that I would be stuck waiting for weeks and weeks and weeks.”

Marni, an architect whose company Marni Evans Sustainability consults on green building projects, is not rich. When we spoke to her, she had “about $600 in the bank” and wasn’t expecting any more income until she signs her next contract. She told us that the costs stemming from the complicated quest to end her pregnancy will likely prevent her and her fiancee from taking the honeymoon trip they had been planning on. But Marni is still more fortunate than many women who find themselves in her position. For women who don’t have any friends in blue states, don’t have the means to get a plane ticket, and don’t have the ability to take any more time off work, the path to obtaining an abortion is lined with even more hurdles.

Having an abortion in Texas is no easy feat to begin with. The state’s forced ultrasound law and 24-hour waiting period ensure that it’s at least a two-day process. Women must make an initial trip to a clinic for a sonogram. They’re required to look at the image of the fetus and listen to the audio of the fetal heartbeat. Their doctor must explain the medical risks of having an abortion and reiterate all of the alternatives to the procedure. Then, women must wait 24 hours before making a second trip to the clinic to actually have the procedure. Even after navigating all of that red tape, low-income Texans can’t always afford to proceed with an abortion — which typically costs about $400 out of pocket — since the state’s Medicaid program won’t cover it.

And this was before the Fifth Circuit’s decision started shutting down Texas’ abortion clinics.

Low-income women who decide to terminate their pregnancies currently face hardship, humiliation or worse before they can obtain the medical care they seek. Many women risk their own health to have an abortion — and were doing so even when there were more clinics available in Texas. Doctors in the state report that many women near the Mexico border are resorting to buying illegal abortion-inducing drugs on the black market, since that’s cheaper and easier than trying to pay multiple visits to a clinic. Now, thanks to the Fifth Circuit, they expect the number of women opting for that potentially dangerous method to rise even further.

This is the landscape facing thousands of women in a nation where the right to choose an abortion is still ostensibly protected by the Constitution itself. “[T]he essential holding of Roe v. Wade should be retained and once again reaffirmed,” according to the Supreme Court’s seminal decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. But for women like Marni Evans in deeply conservative states, the world does not look very different than it would look if Roe had been overruled.

In that alternate universe, where Justice Anthony Kennedy joined with his fellow conservatives to end Roe v. Wade, Marni would still be able to seek an abortion in liberal Seattle, while poorer women would still struggle to obtain the cash and the time off necessary to receive safe medical care — or, worse, they would try to end their pregnancies by taking illegal drugs intended to induce stomach ulcers. The real world and this alternative world are far more similar than Casey‘s promise to reaffirm Roe‘s “essential holding” would suggest. And neither bears much resemblance to a nation where abortion rights are fully protected.

Abortion And Privilege

Before Roe v. Wade, back in the days of botched back-alley abortions that killed alarming numbers of women, a woman’s reproductive autonomy was inextricably linked to her privilege. By the early 1970s, abortion was legal in a handful of states — so if a woman was lucky enough to be born into wealth, she had the resources to travel to one of those areas of the country. If not, she likely resorted to seeking out an illegal abortion. And since women of color were far more likely to be economically disadvantaged at that time, they were also far more likely to lack access to safe abortion. Consider two telling statistics from 1969. That year, 75 percent of the women who died from abortions were women of color. On the other hand, white patients received 90 percent of the legal abortions performed during the same time period.

Four decades later, many of the same dynamics are still at play. Women who can scrape together the money to travel to areas with more permissive abortion laws, women like Marni, are still crossing state lines. Poorer women — particularly low-income women of color, who have less access to affordable planning services and higher rates of unintended pregnancy — aren’t always so lucky.

The Hyde Amendment, the federal policy that prohibits taxpayer dollars from funding abortion services, was enacted just three years after Roe. Abortion access may be a theoretical “right” for every U.S. women — but thanks to Hyde, that right can often only be realized for the women who have money in their bank account. Since poor women’s public insurance coverage won’t cover abortion care, they’re forced to pay for the procedure out of pocket, an expense that can range anywhere between $300 and $3,000 dollars. And, of course, the actual cost of an abortion is much more than that. It also includes the lost wages for the time off work, the potential child care arrangements, the transportation to get to a clinic, and — depending how far a woman has to travel — lodging for the night. Again, this economic reality disproportionately impacts women of color, who are more likely to rely on Medicaid for their health care.

The anti-choice community isn’t succeeding at its ultimate goal of ending all abortion, but its agenda does threaten to eliminate that option for economically disadvantaged women.

That’s because the increasing number of state-level restrictions on abortion only deepen these economic divides. All of the extra hurdles to abortion care — the mandatory ultrasound procedures, the 24-hour waiting periods, the unnecessary regulations on the abortion pill, the restrictions intended to drive clinics out of business — ultimately drive up the cost of this type of reproductive care. It often takes low-income women so long to save up the money for all of the costs associated with their abortion that they run out of time: They’re turned away because their pregnancy is too far along. And it gets worse from there. The women who are denied an abortion are more likely to fall deeper into poverty.

This is the story in Texas, a state with some of the highest rates of uninsurance and unintended pregnancy in the nation. One of the reasons that Marni rushed to book a plane ticket to Seattle was because she didn’t want to endure the ultrasound and waiting period requirements again; she said it was stressful to think about going through that twice, and she was missing too much work waiting in lines at the nearest clinic. Rounds of budget cuts have left a weakened family planning network in Texas, and it’s not uncommon to wait more than four hours at a Planned Parenthood clinic before being seen.

And now, under the new law, it’s even worse. The areas that are losing access to abortion clinics are the same areas with the highest rates of poverty. In huge swaths of Texas, women less fortunate than Marni won’t have any options left. Researchers at the University of Texas estimate that nearly 6,000 women in the state will soon be forced to drive more than 100 miles to get to a clinic. Many of them won’t be able to afford that trip — so, over the course of the upcoming year, an estimated 22,000 women will be denied access to safe and legal abortion care. For them, Roe is more distant than ever before.

A Jurisprudence Of Doubt

Roe was a complicated opinion that is difficult to summarize in a few short sentences, but the gist of it is this: the Court recognized that women have a robust right to an abortion, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy, but that right becomes more qualified as the pregnancy progresses. Nevertheless, the Court recognized abortion as a “fundamental” right — meaning that any law abridging the right would be treated as preemptively unconstitutional. Moreover, while the justices did lay out a framework for when this presumption could be overcome, that framework provided few opportunities to do so during the earliest stages of the pregnancy. During the first trimester, “the attending physician, in consultation with his patient, is free to determine, without regulation by the State, that, in his medical judgment, the patient’s pregnancy should be terminated. If that decision is reached, the judgment may be effectuated by an abortion free of interference by the State.”

Nineteen years later, the justices largely abandoned Roe‘s framework. Though the Court’s 1992 opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey purported to retain Roe‘s “essential holding,” the opinion’s authors went out of their way to express their discomfort with this result. Despite “whatever degree of personal reluctance any of us may have,” the Court wrote in an unusual joint opinion signed by Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy and David Souter, “the stronger argument is for affirming Roe’s central holding.”

Yet, while Casey did not strip women entirely of the rights they gained in Roe, it did qualify those rights significantly. The right to an abortion is no longer treated like a “fundamental” right under Casey. Nor do women in their first trimester of pregnancy enjoy the same robust protection that they once did under Roe. Indeed, where Roe proclaimed that such women enjoy a right to terminate their pregnancies “free of interference by the State,” Casey said the opposite — “it is an overstatement to describe [the abortion right] as a right to decide whether to have an abortion ‘without interference from the State.’”

Under Casey, a new standard would prevail. States are now free to regulate abortion so long as these laws do not impose an “undue burden” on the right to choose.

If you’re confused by the vagueness of this standard, you aren’t the only one. And the Court’s description of what constitutes an “undue burden” does little to clear up this confusion. “An undue burden exists, and therefore a provision of law is invalid,” according to Casey, “if its purpose or effect is to place a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion before the fetus attains viability.” Abortion regulations would no longer be treated as preemptively unconstitutional, but instead would be weighed according to this highly flexible standard by hundreds of judges throughout the country.

Red State Judges Aren’t Like Blue State Judges

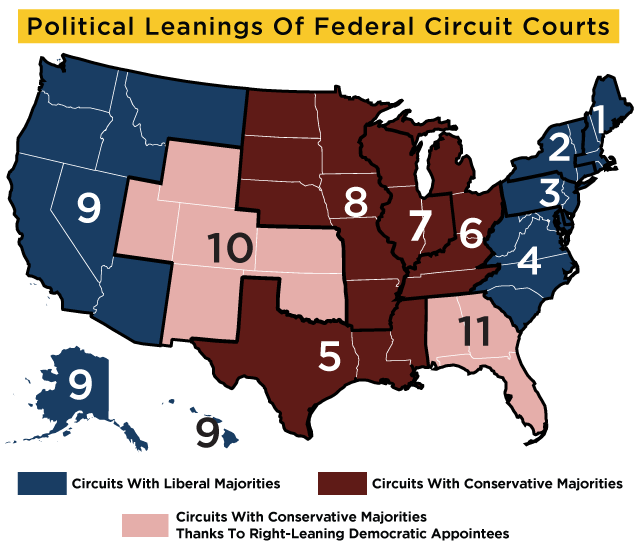

If the significance of Casey‘s vague standard isn’t obvious, consider this map:

That’s a map of the United States split into the 11 federal judicial circuits that determine which appellate court hears most federal lawsuits originating in one of the 50 states. The blue areas on this map represent circuits where a majority of the active federal appellate judges lean left, while the redder areas on the map represent conservative circuits.

There’s not a perfect match between conservative circuits and states that tend to vote Republican, or more liberal circuits and states that tend to vote for Democrats — the Fourth Circuit, for example, is dominated by Clinton and Obama appointees, and it also includes conservative South Carolina — but most voters tend to vote similarly to the circuit judges that preside over their state. Democratic strongholds like New England, New York and the Left Coast are part of the liberal First, Second and Ninth Circuits, while Texas and the deep South sit in the conservative Fifth and Eleventh Circuits. Indeed, the Fifth Circuit, which includes blood red Texas, is probably the most conservative circuit court in the country.

This is not a coincidence. Although the Constitution empowers the president to appoint judges with the consent of a majority of the Senate, a relic of a long-dead patronage system gives home state senators an unusual amount of control over the judges from their own state. Once upon a time, federal judgeships were doled out almost entirely by senators — the White House would typically acquiesce in whoever a state’s senators told them to nominate — and federal circuit judgeships were allocated to specific states so that everyone would know which open seat belonged to which state’s senators. This patronage system was largely dismantled during the Carter and Reagan Administrations, at least with respect to circuit judges, but one remnant of it remains.

Under the Senate Judiciary Committee’s “blue slip” process, a judicial nominee typically will not receive a hearing unless both of the nominee’s home state senators agree to let that hearing move forwards. Thus, a single senator can effectively veto any judicial nominee from their own state. Indeed, there are currently two open seats on the Fifth Circuit that President Obama will likely never be able to fill, unless Senate Judiciary Chair Pat Leahy (D-VT) agrees to suspend the blue slip requirement, because Obama needs Ted Cruz’s permission to confirm anyone to these seats.

So the natural consequence of this blue slip requirement is that states that tend to elect Democratic senators will have more liberal courts while states with Republican senators will have conservative judges. Indeed, the blue slip rule has enabled Republican senators to pressure Democratic presidents into nominating conservative judges to circuit judgeships in their state — as the senators have the power to veto anyone nominated to that seat by a president of the opposite party. A majority of the active judges on the Eleventh Circuit were appointed by Presidents Clinton or Obama, but the court remains very conservative thanks to the blue slip’s power to force presidents to name compromise nominees. Similarly, the Tenth Circuit’s active bench is evenly split between Democratic and Republican appointees, but an Obama-appointee named Robert Bacharach recently sided with conservatives in a major birth control case that is now being heard by the Supreme Court. Judge Bacharach joined the court with conservative Sen. Tom Coburn’s (R-OK) enthusiastic support.

Combine the blue slip’s ability to move red state courts to the right with Casey‘s vague standard, and that means that the states that are most likely to enact restrictive abortion laws are also the states that are least likely to have judges willing to overturn those laws. As appellate courts typically rely on randomly drawn three-judge panels to decide cases, it is still possible to draw a liberal panel in a conservative court or vice-versa — but that does nothing to change the fact that a woman in California is overwhelmingly more likely to have her case heard by a pro choice panel than a woman in Texas.

Enter Priscilla Owen

Fifth Circuit Judge Priscilla Owen was what is euphemistically known as a “controversial nominee” before a group of Senate Democrats allowed her to be confirmed in an ill-considered effort to ward off filibuster reform. As a Texas Supreme Court justice, Owen took thousands of dollars in campaign donations from Enron — yes, THAT Enron — and then authored an opinion reducing the company’s taxes by $15 million. She fought to limit abortion rights in a way that her fellow Justice Alberto Gonzales described as an “unconscionable act of judicial activism“. Yes, THAT Alberto Gonzales.

So there really wasn’t much question how Owen would vote when she was asked to consider Texas’ new law requiring doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges in an nearby hospital.

If Roe v. Wade were still good law — that is, if abortion were still considered a “fundamental” right and laws abridging the right were still treated as preemptively unconstitutional — then no judge acting in good faith could have upheld the Texas law. As the trial court judge explained in his opinion blocking this provision of Texas law, “there is no rational relationship between improved patient outcomes and hospital admitting privileges.” Emergency room doctors “treat patients of physicians with admitting privileges no differently than patients of physicians without admitting privileges. Admitting privileges make no difference in the quality of care received by an abortion patient in an emergency room, and abortion patients are treated the same as all other patients who present to an emergency room.” Thousands of women will be unable to obtain an abortion because of Texas’ new law, and the law does little, if anything, to protect women’s health.

But, of course, Roe is not good law, Casey is, and Judge Owen had no trouble wielding Casey‘s vague standard to achieve the result she desired. Owen brushed off the evidence that more than 22,000 women would be denied care thanks to Texas’ law, concluding instead that “the provisions of H.B. 2 requiring a physician who performs an abortion to have admitting privileges at a hospital . . . do not impose a substantial obstacle to abortions.”

A Grim Future For Choice

At an event co-sponsored by the Center for American Progress in 2010, former acting Solicitor General Walter Dellinger warned that what’s left of Roe v. Wade may not survive the coming decade. “For a while,” Dellinger explained, he thought that the Roberts Court would “simply chip away and allow more and more regulations that sort of protected access for the most affluent women but really made it impossible for women who were vulnerable to geography, poverty [and] youth” to obtain abortions. Now, however, Roe has become “such a symbol of a kind of jurisprudence that conservatives have set themselves in opposition to . . . that someone who feels that way would think we can’t straighten out jurisprudence until we actually say the words ‘Roe v. Wade is overruled.”

Dellinger was envisioning a Court where Justice Kennedy’s been replaced by an even more conservative justice, but the truth is that the Court’s been inching in this direction for quite some time. Though Kennedy is widely perceived as the swing vote on abortion because he provided the key fifth vote not to toss out the right to choose entirely in Casey, this perception in not really grounded in evidence. Rather, as David Cohen explains in Slate, Kennedy “has voted to strike down only one of the 21 abortion restrictions that have come before the Supreme Court since he became a justice.” Moreover, the sole provision he voted to block was a Pennsylvania law requiring married pregnant women to notify their husbands before obtaining an abortion that was at issue in Casey. In other words, Kennedy has not voted to block a law restricting access to abortion for the last 21 years!

Beyond Casey, Kennedy’s most consequential abortion opinion is Gonzales v. Carhardt. Though pro choice advocates highlight Gonzales as an example of the Court’s condescending attitude towards women — Kennedy wrote that the right to choose should be narrowed because “some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained” — the 2007 opinion is just as significant for the devil-may-care attitude it takes towards physicians’ medical judgment.

Gonzales upheld a ban on a procedure known as “intact dilation and extraction,” which many physicians believe is the safest way to terminate a pregnancy in certain cases. Beginning with Roe, the Court was reluctant to allow policymakers to second-guess a doctor’s medical judgment. This is why Roe held that during the first trimester “the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman’s attending physician,” and it is also why Roe established that abortions must be allowed even in the late stages of pregnancy “where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”

Kennedy’s opinion in Gonzales, however, gives lawmakers “wide discretion to pass legislation in areas where there is medical and scientific uncertainty.” The upshot is that the question of how to protect a woman’s health during an abortion is no longer left entirely to her doctor — much of it is now left to members of Congress or state lawmakers who are free to resolve “uncertainty” among physicians in favor of their personal policy preferences.

Nor is it likely that Gonzales represents the height of Kennedy’s willingness to permit restrictions on abortion. To the contrary, while Kennedy did not explain his reasons for doing so, Kennedy denied a request last week to stay Judge Owen’s decision in the Texas case. And remember, Kennedy co-signed the Court’s opinion in Casey — an opinion that alluded to what was almost certainly his own “personal reluctance” to uphold Roe v. Wade. There is some daylight between Judge Owen and Justice Kennedy on the subject of abortion, but the sun has still set pretty far on the right to choose.

The Women Left Behind

When we checked in again with Marni, three weeks after we first spoke to her, she told us that she had successfully had an abortion. And then she told us something else that drove home just how much the right to choose can depend upon whether the woman exercising that right is wealthy, fortunate or, in Marni’s case, unusually savvy.

She actually ended up being able to have the procedure in Austin — and she emphasized that was because she’s very lucky. “It was thanks to my increased visibility and the connections that came out of that,” she explained.

After Marni’s abortion appointment was canceled, ThinkProgress wasn’t the only media outlet she contacted. She spoke to several outlets, got connected to some of the women’s health organizations in the state, and even ended up appearing on a conference call hosted by Planned Parenthood to help provide more context for the immediate impact of Texas’ harsh new law. She met a lot of people who knew more about the landscape in Texas than she did — including Amy Hagstrom Miller, the founder and CEO of Whole Women’s Health, who booked Marni an appointment at one of the clinics she operates.

Without that assistance, Marni told us, she wouldn’t have known where to turn. In the immediate aftermath of Texas’ new abortion restrictions, most clinics’ websites hadn’t yet been updated to reflect whether they were still open. It was hard to tell whether a website was advertising an abortion clinic or a “crisis pregnancy center” — right-wing organizations masquerading as comprehensive health clinics that don’t actually provide abortions and often spread misinformation about health care services. It was overwhelming. But with Hagstrom Miller’s help, Marni was able to visit a clinic in Austin, bypass the long lines, and get the abortion care she needed.

Again, Marni isn’t rich; she told us she was especially grateful to have found an abortion clinic in Austin because her trip to Seattle was looking less likely by the day. She wasn’t confident she could afford the plane ticket back to Texas, and she definitely didn’t have enough money to allow her fiancee to travel with her.

But even though she’s not financially well-off, she’s still privileged. Marni is educated, media savvy, and connected — and she got her abortion. Although the process of exercising her right to choose was certainly a struggle, the right still exists for Marni.

But that’s simply not the case for many other Texas women who received the same phone call Marni did they night of the Fifth Circuit’s decision — and for thousands of other women who will be unable to obtain an abortion in the wake of that decision. The idea that every single woman seeking an abortion can catch the eye of a reporter and eventually be noticed by the CEO of a women’s health clinic is absurd. And even if that were possible, women hoping to terminate their pregnancies in Texas now have to compete for the time of a diminishing group of physicians who are legally permitted to perform abortions. Although four of Whole Woman’s Health’s five clinics remain open, some clinics that previously had three or four physicians on staff now have only one doctor with the admitting privileges required by the Texas law.

Not long after the Fifth Circuit’s decision was handed down, RH Reality Check detailed some of these women’s stories. Suzy, a mother of three, discovered that her appointment had been canceled after she had already pushed back the procedure multiple times to raise enough money for it. At the beginning of November, Suzy was already 19 weeks pregnant and running out of options — particularly since another piece of Texas’ omnibus new anti-abortion law bans abortions later than 20 weeks. Mary, a survivor of sexual assault, planned to have an abortion because she “cannot bear the thought of her rapist’s child,” but was forced to delay the procedure after her appointment was canceled. And Elena, a mother of three who scheduled her abortion for the beginning of November because she needed to put part of her October 31 paycheck toward the cost of the procedure, had to search for another clinic.

For those women, and the hundreds of others like them, rescheduling these appointments is much easier said than done. Elena, for instance, lives in the Rio Grande Valley — a rural border community where the closest abortion clinics are now 150 miles away. As soon as Texas passed its new abortion restrictions over the summer, it was pretty clear that the women living in the Rio Grande would be stranded far away from their right to choose, a new reality that media outlets have been freely acknowledging for months.

“For the border region of the Rio Grande Valley, this means women will have little choice but to turn to dangerous alternatives to deal with an unwanted pregnancy,” Texas Public Radio reported in July, noting that they’ll likely opt to buy abortion-inducing drugs at black market pharmacies in Mexico. “The only option left for many women will be to go get those pills at a flea market. Some of them will end up in the ER,” Lucy Felix, a community educator with the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, told the New York Times. In August, the Texas Tribune reported an uptick in the number of women crossing the border for exactly this reason.

Amid the tattered remains of Roe v. Wade, these women are left behind. They’re living in the reality that Dellinger was referencing, the world in which affluent women may exercise their right to choose while impoverished women may not. It’s a world that Texas’ Republican officials were all too happy to embrace, and that they’re ready to keep fighting for in court. And it doesn’t look too different from 1972.

Andrew Breiner contributed graphic design to this article

Leave a Reply